Listen to This Blog Post

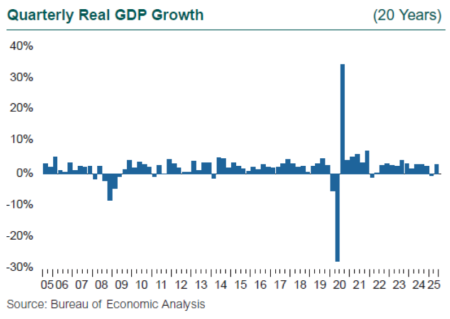

2Q25 was certainly eventful from a policy and capital markets perspective, but the U.S. economy continued to sail on with strong growth, notching a gain of 3% (annual rate), 1% higher than consensus. As we pore over the data for 2Q (and revised data for 1Q), we are hard-pressed to find evidence of the impact of the Trump administration’s tariff policy.

Given the constant revisions to tariff rates, to the sectors and countries to which they will be applied, and to their timing, that is not surprising. Investor and consumer sentiment has been both hammered and elated, sometimes within the same week, even the same day, and we saw tremendous volatility in the public stock and bond markets as the second quarter evolved. The stock market legged down in 1Q and the bottom dropped out the first weeks of April, as investors feared a trade war and recession. Intensifying war in Gaza and Ukraine added to the anxiety. The bond market exercised its muscle in response to the policy announcements, with a sell-off and rising interest rates. The power of the bond market to penalize what it perceives to be adverse government policy should not be underestimated. Countless presidents and members of Congress have learned this lesson the hard way over post-WWII history.

How the 2Q25 U.S. economy performed

By the end of June, the S&P 500 had rebounded from its 4.3% loss in 1Q to show a 10.9% 2Q gain. Investors have indicated that while they are ultimately sensitive to tariff policy, they are willing to look past the variable implementation of 2Q, and their behavior may indicate a belief that trade accommodations will be reached eventually. The global ex-U.S. equity markets showed their long-dormant potential to diversify U.S. equities in 2025, with the MSCI ACWI ex-USA Index posting a gain of 5.2% in 1Q and 12% in 2Q. The challenge for investors is how tariff policy, economic growth, and inflation will interact, and how the Federal Reserve will respond via interest rate policy.

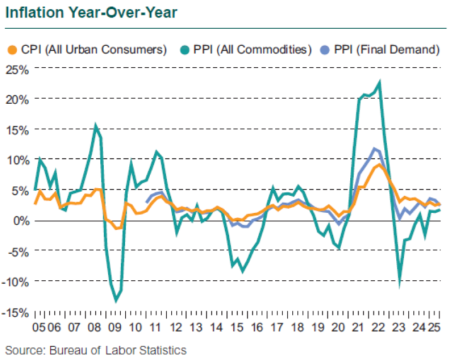

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has stated the Fed would likely have cut interest rates by June this year if not for the uncertainty of tariff policy. Inflation came in at 2.9% in June, an uptick from 2.7% in March, but evidence of tariffs on prices is hard to discern at this point. Shelter costs dominate in the upward pressure on prices, while energy has been a strong downward influence over the past year. New auto prices showed a 5% uptick, and select industrial machinery and electronics showed annual price gains in the 3% to 10% range, but none of these stand out as substantial drivers. The changes in the timing and rates for tariffs may have delayed the impact, but the tariff agreements announced since the end of 2Q will soon push up prices for these imported goods; consumers’ response to higher prices will determine the real impact as they reduce purchases or substitute away from the tariffed goods.

The strength in the U.S. economy through June surprised nearly everyone and seems to counter the case for lower interest rates, even with the tariff uncertainty. Consumption, which makes up 70% of GDP, dipped to a growth rate of 0.4% in 1Q, but climbed back to 1.4% in 2Q. Companies built inventories like mad in 4Q24 and 1Q25, which gave a boost to GDP, while inventories were drawn down in 2Q, reducing both potential production and measured GDP. Consumer confidence has rebounded after a drop in March and April and has been supported by a continuing low unemployment rate (4.1%), real wage growth (inflationary but good for household incomes), and no signs yet of a feared spike in inflation.

The controversial data point raising eyebrows after the close of 2Q is the revision to the May and June monthly employment data. After reporting healthy gains in excess of 100,000 jobs in each of May and June in the initial report, the revision, released with the July jobs report, removed almost 260,000 new jobs from the May and June data, reducing job gains for these two months to close to zero. Job numbers are based on surveys of employers and are subject to a number of revisions in subsequent months. These revisions were the largest in years, spurring questions about the timely reporting of monthly jobs data. Economists generally understand the challenges with the survey process and believe the current BLS practice is sound. Over history, the biggest monthly revisions come at turning points in the economy: large downward revisions while a cycle cools, and large upward revisions as the economy emerges from a slowdown and the data cannot keep up with new job creation from new employers.

Businesses and investors, however, loathe uncertainty, especially when it comes to capital investment. At the moment, there is great value to sitting tight and waiting for policy to unfold rather than moving forward and stranding assets with the wrong call on tariffs (either rates, countries, or sectors), or on inflation. Sitting tight will eventually weigh on economic growth.

One continuing point of confusion is the role of imports in GDP. The common misconception is that imports are a negative in the calculation of GDP, and that a reduction in imports reduces a negative number and therefore contributes to GDP growth. Imports do not contribute to GDP. Gross Domestic Product measures the collective production within a country. Imported goods and services are not produced with the domestic economy and cannot add to GDP directly.

Imports can and do affect GDP indirectly, which is what tariff policy is intended to address. The choice to import a car does not contribute to GDP in the quarter of purchase. But the choice to import likely means that a domestic car was not purchased, so the import indirectly led to a decline in GDP.

Disclosures

The Callan Institute (the “Institute”) is, and will be, the sole owner and copyright holder of all material prepared or developed by the Institute. No party has the right to reproduce, revise, resell, disseminate externally, disseminate to any affiliate firms, or post on internal websites any part of any material prepared or developed by the Institute, without the Institute’s permission. Institute clients only have the right to utilize such material internally in their business.