Listen to This Blog Post

This blog post, and a white paper to follow, will introduce the concept and outline the pros and cons of incorporating risk-mitigating strategies (RMS) into institutional portfolios, and the paper and future blog posts will recommend a blended approach depending on risk tolerance, level of protection desired, and liquidity needs.

RMS Introduction

The market environment since 2020 has highlighted the shifting sensitivity of both the market and institutional portfolios to inflation, rising interest rates, equity and fixed income correlation, and bouts of increased equity volatility. During this time, institutional investors have sought ways to protect portfolios from volatility and drawdowns associated with certain market events, as well as the liquidity challenges that such events may pose.

A small subset of institutional investors have reimagined their hedge fund portfolios to focus on these objectives, and the resulting concept is what is collectively known as risk-mitigating strategies. The goal of my blog post and white paper is to explore the concept of risk-mitigating strategies and develop a framework that is flexible enough to address diverse client needs.

What Are RMS?

Risk-mitigating strategies are investments that, to varying degrees:

- Protect a broader portfolio from larger drawdowns

- Provide diversification

- Offer liquidity during high-risk market environments

- Have a positive long-term expected return

In most cases, equity exposure is the primary source of “economic growth” risk for institutional portfolios, so most RMS portfolios are designed to mitigate this specific risk. RMS investments are usually comprised of alternative investment strategies that have exhibited low to negative correlations to equities, with the caveat that correlations may change during negative economic shock events.

Why Are RMS Being Adopted?

Institutional portfolios are seeking to redesign or tweak hedge fund portfolios to address two objectives (diversification and liquidity) specifically.

Investors understand that curtailing drawdowns over a long period will allow returns to compound more effectively, thereby improving overall performance and funded status.

In a simple example, suppose you have two equivalent portfolios, but one experiences a 30% loss every 10 years over 20 years (Portfolio A) while the other experiences a 20% loss every 10 years over the same time (Portfolio B). Portfolio B would need to only earn 6.48% annualized while Portfolio A would need to earn 8% to achieve the same asset level. This is primarily due to Portfolio B’s ability to compound returns from a higher asset level. Albert Einstein was on to something when he described compounding as “the eighth wonder of the world.”

Investors also seek to avoid using liquid assets that have experienced recent declines to fund current liabilities or previous capital commitments.

Most CIOs are aware of the need to fund retiree benefits and do not want to “sell equities after a sell-off” or, even worse, be forced to raise cash from other more illiquid asset classes to fund capital calls for other illiquid, long-term commitments.

What Are the Largest Institutional Investors Implementing an RMS Portfolio?

CalSTRS, the largest educator-only pension fund, has allocated 8% of its portfolio to risk-mitigating strategies, with a target allocation of 10%. This is based on a total of $358.4 billion.

Other large public institutional investors include:

- Maryland State Retirement and Pension System ($66B)

- Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds ($55B)

- Employees’ Retirement System of the State of Hawaii ($23B)

These RMS implementation and plan assets are based on publicly available information as of May 31, 2025.

How Are RMS Portfolios Being Implemented?

Current practices highlight five primary categories in an RMS framework:

- Long Treasuries: Lock in a long-term interest rate on what are among the safest investments

- Global Macro: Can anticipate regime shifts or changes in the economic cycle through analysis of real-time macroeconomic data across sectors/geographies

- Trend-Following: Systematic investing in futures markets that attempts to exploit trends in price movements

- Long Volatility and Tail Risk Protection: Long volatility, known as “long vol,” can employ arbitrage, directional, or market-neutral strategies on implied vs. realized volatility. Tail risk protection focuses on protecting against a specific level of drawdown, usually at a percentage of current levels.

- Alternative Risk Premia: Low-cost, systematic strategies designed to provide diversification to equities

What Are the Pros and Cons of Implementing an RMS Portfolio?

Pros

Buying low, not selling low: As noted previously, the main objective of an RMS portfolio is to protect a broader portfolio from larger drawdowns by providing diversification and liquidity during high-risk market environments.

Liquidity is a critical component, as it provides the ability to not “sell when an asset is down,” but also gives the option to “buy more when the asset is down.” Long-term portfolio outperformance can be turbo-charged with the ability to buy assets at temporarily lower prices.

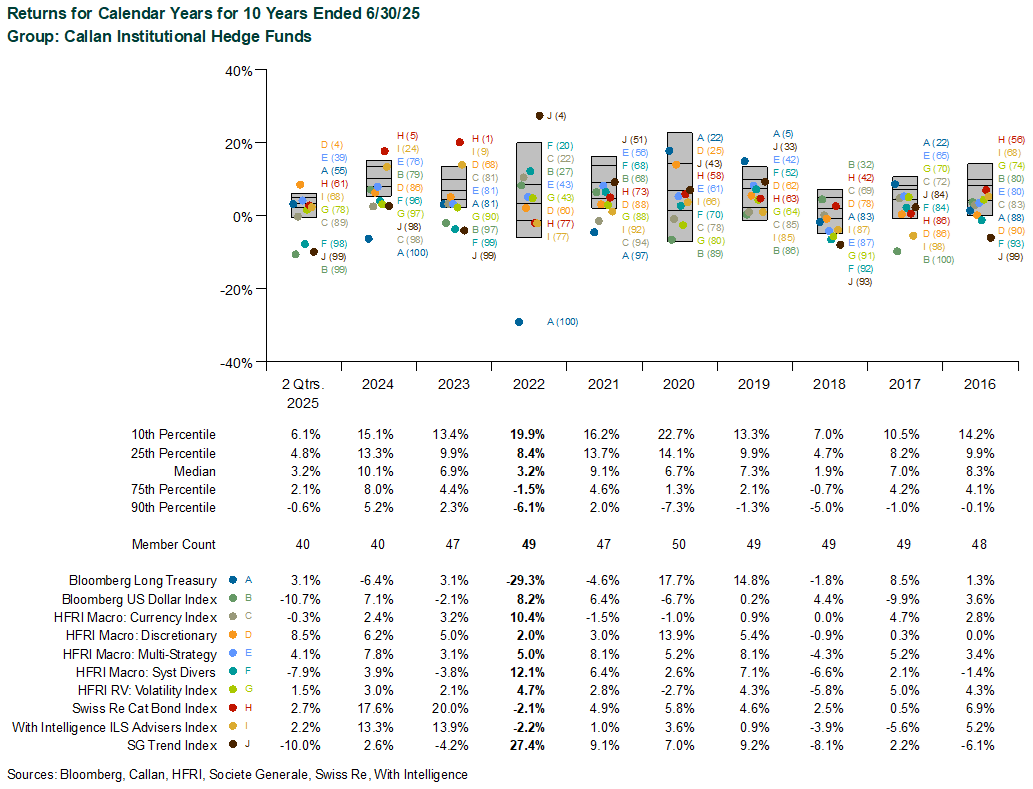

Additional diversification: A focus on strategies that diversify equities, other than a traditional fixed-income portfolio, will provide additional improvements to an optimal portfolio in a mean-variance framework. Investors experienced sizable declines in both asset classes as recently as 2022, when the Fed moved aggressively to increase interest rates to combat inflation. As an asset class, hedge funds shone that year after struggling for more than a decade. Certain RMS portfolios, particularly ones that featured trend-following, systematic macro, and long dollar strategies while avoiding long Treasuries, tail risk, and long vol, had success during the year.

More upheaval likely: Some market participants warn that future uncertainty is expected to be more prevalent than in the past several decades. With geopolitical considerations and the recent trend away from globalization, it is rational for investors to expect more volatility and macroeconomic shocks like the ones that have resulted in the large equity sell-offs that we have seen, on average, once a decade for the past 50 years. Furthermore, these sell-offs have become more sudden, thanks to changes in market liquidity due to the evolution of so-called dark pools, which are private exchanges for securities trading, the prevalence of algorithmic trading, and crowding from highly leveraged platform managers. RMS strategies attempt to address these risks, albeit somewhat indirectly.

Cons

Opportunity cost: The loss of performance due to the allocation to an RMS portfolio that would otherwise be allocated to the strategic portfolio or other opportunistic investments.

RMS portfolios are expected to yield a lower return in non-stressed periods (which is most of the time) as they forgo growth exposure in favor of strategies that provide liquidity and/or outperformance during market sell-offs. In periods of extended market outperformance and/or the absence of market volatility, such as the decade following the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, the underperformance can be more pronounced.

Furthermore, RMS component strategies are generally more expensive than traditional public markets strategies and in some cases sacrifice generating long-term alpha for short-term protection in extreme market environments.

Added portfolio complexity: RMS portfolios require strong governance and specialized personnel who are familiar with such strategies, as well as operational expertise that may only be found in larger or well-resourced organizations.

Implementation issues: It is challenging to select top-performing managers for widely utilized RMS strategies, such as long vol, tail risk, and trend-following.

Lack of capacity among capable managers: For example, among multi-strategy managers, only a handful have achieved long-run return goals, and those that have are often closed or capacity-constrained.

Trading one risk for another: Some low-correlated, high Sharpe ratio hedge fund strategies, such as fixed income arbitrage, insurance-linked securities, or relative-value interest rate trading, have unobservable, or difficult to quantify, tail risks.

Monetizing hedges (market timing): This is tough to do, even when you are invested in the right RMS strategy. Does the institutional investor delegate discretion to the manager or want to keep hedges to protect from further downside? Sound governance is essential to addressing this problem.

Institutional client reluctance: Very few clients will pay for tail risk protection, especially on an ongoing basis in the case of long volatility strategies. Long-term board consistency helps to hold such a portfolio during extended periods when the market is not rewarding this strategy. But it is not the natural order in the realm of public funds.

Both facts contribute to the stories of institutional investors abandoning an RMS program in the absence of market turmoil, only to regret it once a negative market shock occurs.

Benchmarking can be a problem: For some, typically the higher convexity strategies, it is challenging to determine the type of protection being purchased. With more complicated strategies, even the most meticulously designed portfolio might not perform as intended.

In some cases, one can only determine the result given a certain path dependency.

- Investors seeking a certain payoff of the RMS portfolio are partially at the mercy of chance, depending on where markets end up versus where their portfolio’s convexity kicks in.

- For off-the-shelf RMS solutions, there is an inherent agency problem with building such portfolios.

- Who is selling these portfolios, and how do they stand to gain?

- Are interests aligned? Who will answer for the portfolio if/when it doesn’t perform?

- For truly customized portfolios, a complex but logical benchmarking solution relies on custom benchmarks based on a well-known index provider, such as Goldman Sachs-Bloomberg, or HFRI strategy-level indices, coupled with traditional asset-specific indices such as the Bloomberg Long Government Bond or the S&P GSCI Gold Index (to benchmark Treasuries and gold, respectively).

- Sound governance requires an investment policy statement (IPS) for the RMS portfolio.

In future blog posts, I will discuss the merits and considerations of each sub-strategy as a framework for building an RMS portfolio and outline an approach to building a blended portfolio that suits an institutional investor’s risk tolerance, desired level of protection, and liquidity needs. Additionally, I will explain how to address the implementation challenges and put into perspective the opportunity costs.

Disclosures

The Callan Institute (the “Institute”) is, and will be, the sole owner and copyright holder of all material prepared or developed by the Institute. No party has the right to reproduce, revise, resell, disseminate externally, disseminate to any affiliate firms, or post on internal websites any part of any material prepared or developed by the Institute, without the Institute’s permission. Institute clients only have the right to utilize such material internally in their business.